Illegal mining is surrounding and entering Cofán Bermejo, as revealed by satellite images and deforestation alerts from the Global Forest Watch platform.

In the north of the Ecuadorian Amazon there are five protected areas that are home to enormous areas of biodiversity: the Yasuní, Cayambe Coca, Sumaco Napo-Galeras national parks, the Cuyabeno fauna production reserve, and the Cofán Bermejo ecological reserve.

Right in the middle of these protected areas is Lago Agrio, a city in the province of Sucumbíos considered to be the oil capital of Ecuador. And because of that, despite the destination of large extensions of land dedicated to conservation, the northern Amazon, mainly the provinces of Sucumbíos and Orellana, also concentrates the largest oil activity in the country.

A recent report by the organization Amazon Frontlines indicates that, since the oil industry established itself in the Ecuadorian Amazon in the 1970s, more than 647,000 hectares of primary tropical forest have been cleared for oil infrastructure, roads and the colonization that arose later. “Satellite images show that more than 370,000 acres [more than 149,000 hectares] have been cleared in the last 20 years in a 30-mile [48-kilometer] radius around the oil city of Lago Agrio, where the first wells [were drilled],” the report says.

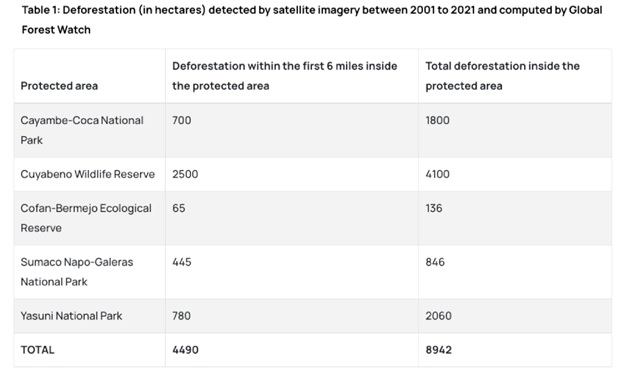

The same analysis mentions that not even the five protected areas near Lago Agrio have prevented deforestation from entering the territories they sought to protect when they were declared. For example, between 2001 and 2021, Cuyabeno has lost 4,700 hectares of forest, followed by Yasuní with 2,060.

Until now, the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve had been the least affected by the felling of primary Amazon rainforest —136 hectares in 21 years—, but recent alerts from the Global Forest Watch platform show that this situation is changing.

The analysis carried out by Mongabay Latam on this platform showed that in the last two years, when deforestation began with more force in this area, 2,747 deforestation alerts have been registered. However, between January and the first week of October 2022 alone, 1,531 of these alerts were registered on the border between the Cofán-Bermejo reserve and the A’i Cofán indigenous territories. According to this monitoring, deforestation begins in February and has extended until the first week of October. However, it is in the month of September when the highest number of alerts is recorded. What’s going on?

Deforestation in protected areas in hectares detected by satellite images, between 2001 and 2021, in five protected areas in the north of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Second column: hectares deforested in the first 10 km inside the protected area. Third column: Total deforested hectares within the protected area. Source: Amazon Frontlines.

Illegal mining and the fear of denouncing

The historical conservation of the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve has not been fortuitous.

Nicolás Mainville, biologist and Territorial Defense coordinator for Amazon Frontlines, explains that there are several factors that have helped this to remain the case until recently. This is due “to its location very far from urban centers, that it is right on the border with Colombia and that oil exploitation, together with the highways, have not yet arrived,” says Mainville.

The problem is that illegal mining did begin to knock on the doors of this protected area created in 2002 and the situation has become quite complicated. Sources in indigenous communities and experts consulted by Mongabay Latam say that security in Cofán Bermejo and its surroundings is critical because, being on the border with Colombia, various criminal and drug trafficking groups operate there.

“We don’t know if the illegal miners are part of these groups or have a relationship with them,” says an indigenous person who lives in the area and who prefers not to reveal his identity for fear of reprisals.

Fear is the constant in this border region. That is why, even though several indigenous communities live in the surroundings and within the protected area, they have not dared to publicly denounce what is happening there.

Satellite images from August 2022 show deforestation caused by illegal mining outside and within the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve. Image from Amazon Frontlines.

Several indigenous people told Mongabay Latam that it all started with foreign people who arrived in the ancestral territories that are on the edge of the reserve and began illegally exploiting wood. Then came mining and this is what is now out of control.

An expert from an organization that knows the area but prefers to keep its name confidential due to the difficult security situation there, says that illegal mining began to expand in the Bermejo River in 2020. “There is a presence of machinery and deforestation on the banks. A drastic change in the riverbed due to the presence of bulldozers and large motor pumps. You can see the miners, people who are not from that area,” he says.

Navigation in one of the rivers that crosses the Cofán Bermejo Reserve. Photograph taken from the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve Facebook page.

Satellite images analyzed by the Amazon Frontlines organization show how, in August of this year, the situation spilled over, since not only was there a rapid increase in mining activity on the limits of Cofán Bermejo, and illegal mining had already entered it.

The indigenous and mestizo communities in the area are concerned about the effects on the Bermejo River, but also on the San Miguel and Sarayaku rivers. Many of these populations are fishermen and, they say, they already feel the negative effects in the water.

“At the junction of the Bermejo River with the San Miguel River, there has been a drastic drop in the number of fish, which affects fishing communities. The water is very cloudy, and the levels are very low,” said the consulted expert.

Indigenous people and inhabitants of mestizo communities that live near the Bermejo River say that for about a year they have been seeing changes in the color of the waters and have noticed a lower flow that makes it impossible to navigate by boat in many sections.

“The Ministry of the Environment is aware of this serious situation but is currently not doing anything. We as communities see this whole situation, but we are at great risk and we don’t know how to act,” says a community member.

The indigenous also say that “due to the complexity of the area, the communities are observing the situation, but it is the State that has the obligation to act against these threats. If it does not, we will have to think about how to protect the rivers and territories.”

Mongabay Latam contacted the Ministry of Environment, Water and Ecological Transition (MAATE) to ask about the actions they are implementing to confront illegal mining and prevent Cofán Bermejo from becoming a new source of contamination and accelerated deforestation as happened at the beginning of this year with the Yutzupino River in Napo province.

In an official response, the MAATE replied that illegal gold mining has been carried out for approximately 10 years in the Cáscales sector, province of Sucumbíos, gaining strength during the pandemic, and that for two years entry has been made difficult by that sector, without allowing MAATE officials to enter, “however, the entrance for the respective controls is made through another place.”

“It is known that illegal mining activities are being carried out in the Bermejo River in the buffer zone of the Cofán Bermejo reserve, in the Etsa community,” the Ministry replied.

The entity said that on March 5, 2022, the staff of the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve responded to a complaint of illegal mining that was presented via WhatsApp, in which they were told that this activity would be carried out within the protected area. After inspecting, it was possible to verify the activity in two points, one of them inside the reserve. In addition, the MAATE reported that on March 10th, in the jungle battalion 56 Tungurahua, it exposed the problem of illegal mining in the Cáscales sector.

After this they continued to receive complaints and in four inspections they found abandoned camps, heavy machinery, dredgers and motors with 2-inch hydraulic hoses, in addition to a five-hectare area “where anti-technical mining activity is observed that affects vegetation cover.” According to the Ministry, on April 14th they asked the Ministry of Government to convene the Special Commission for the Control of Illegal Mining (CECMI), but they did not report if that meeting has already taken place or when it will take place.

“Likewise, in the month of September 2022, meetings were held with the zonal directorate 9 of the MAATE, the ministerial office and the government of Sucumbíos, in order to better articulate the actions to be carried out in terms of control in the zone of Cáscales, reaching consensus that the Regional GAD would inform the CECMI authorities of the intelligence reports raised by said administrative unit,” said the MAATE. However, the entity did not provide more details about the results of these consensuses.

Landscape in the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve. Photograph taken from the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve Facebook page.

Mining concessions in process in the Bermejo River

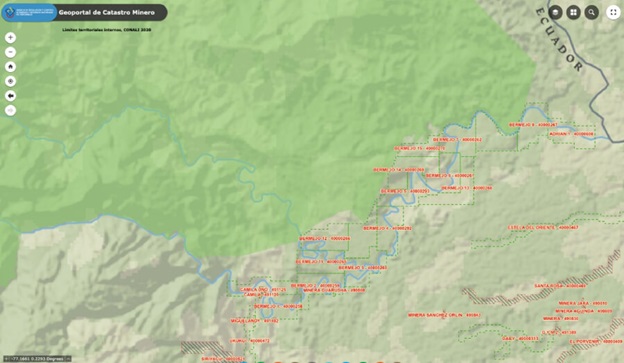

Illegal mining is not the only problem facing the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve. When reviewing the Ecuadorian Mining Registry, the organization Amazon Frontlines realized that, at this moment, there are 23 mining concessions in process on the Bermejo River, in the southeastern limit of the protected area. All of them are for gold exploitation.

Although the requested concessions are for small-scale mining and artisanal mining, Nicolas Mainville says that the communities and the protected area will suffer a direct impact since the Bermejo River enters the ecological reserve and carries with it all the contamination that it received upstream, affecting the flora and aquatic fauna, as well as fishing and the drinking water of many communities.

Concessions in process on the Bermejo River, touching the limits of the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve. Image taken from the geoportal of the Mining Registry of Ecuador.

“There are more than 5,300 hectares of mining concessions in process just above the Bermejo River and another nearby, concessions that were entered in the Mining Registry without any prior consultation. It is a very similar situation to what happened in Sinangoe four years ago,” says Mainville.

The biologist refers to the case of the Cofán de Sinangoe indigenous territory, within the Cayambe Coca National Park. In 2018, the community realized that illegal miners were extracting gold from the Aguarico River, within their ancestral territory, and that they had already affected between 15 and 20 hectares.

“In Cofán Bermejo there is about four or five times more [illegal mining] activity than in the case of Sinangoe,” says the expert consulted who requested that his name be withheld.

Sloth release in the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve. Photograph taken from the MAATE Twitter account.

Once the Sinangoe community detected illegal mining, they began to investigate and realized that legal mining was also intended to be carried out on their territory since, according to the Mining Registry, 20 concessions had already been approved and 32 more were in process.

The Sinangoe began a legal battle to defend their territory. In October 2018, the Ecuadorian justice decided to revoke the 52 concessions. In February 2022, the Constitutional Court ruled in favor of the right to prior, free and informed consultation of the indigenous peoples and nationalities, taking as a reference the legal action presented by the Cofán of Sinangoe, where they claimed that they were not consulted about the concessions mining on their ancestral lands.

Mongabay Latam asked MAATE about the legality of the concessions that are being processed near the Cofán Bermejo Reserve and in the territory of several indigenous communities, as well as the lack of prior consultation. MAATE insisted that “according to the updated Mining Registry as of August 31, 2022, the mining concessions referred to are in the process of being granted to the respective mining titleholders in the Sectorial Ministry, which is why have started a regularization process in this State portfolio.”

“The State usually says that we indigenous people oppose legal mining in order to allow illegal mining, but that is totally false. They try to delegitimize the struggle of the peoples. We do not want the illegal nor the legal. In the legal part we have some tools to assert our rights, but in the illegal, we are totally unprotected,” says the indigenous person who asked to reserve his name.

“The value of Cofán Bermejo at the conservation level is much higher than the value that the grams of gold extracted from those concessions could have,” says Mainville.

This report was originally published on Mongabay Latam

It is absolutely ridiculous that there are ANY mining concessions in an area that effects water, let alone tribal areas.

May I suggest monitoring the protected areas with drones. You will be able to identify the illegal mining activity safely. As well as document the criminal activity.

This is unacceptable. The government must do it’s job and stop this corruption instaed of being any part of it.