Mining activity, both legal and illegal, covered more than 7,495 hectares in the Ecuadorian Amazon in 2021, the most recent date analyzed in the study by the Andean Amazon Monitoring Project (MAAP) and the Ecociencia Foundation.

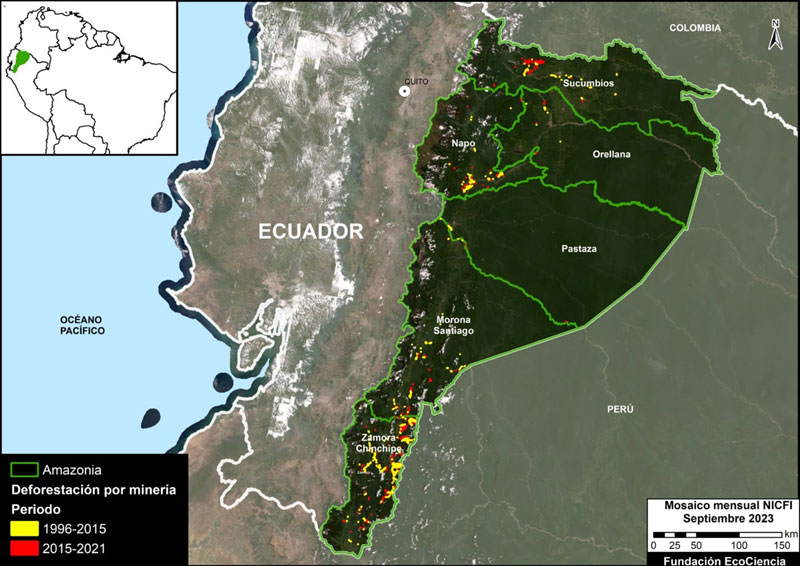

The most affected provinces are Zamora Chinchipe, Napo, and Sucumbíos. At least 46.7% of the mining detected in the Ecuadorian Amazon is located in indigenous territories.

The Ecuadorian Amazon, which covers more than 51% of the country’s territory, is being threatened by both legal and illegal mining. A study published by the Andean Amazon Monitoring project (MAAP) and the Ecociencia Foundation, with data updated through 2021, shows that in that region, mining activity covers an area of 7,495 hectares, an area larger than the territory of the island of Bermuda.

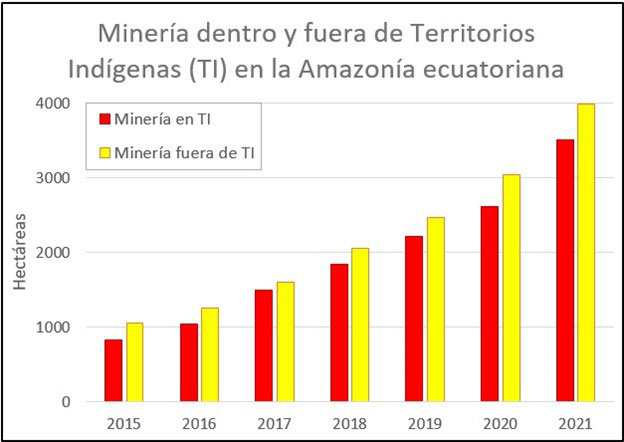

The situation is worrying. In 2015, mining activity occupied 1,879 hectares, but by 2021 it expanded by 5,616 more hectares; that is, there was a growth of almost 300% in that period.

Zamora Chinchipe is the province with the largest area dedicated to mining: 5,034 hectares, representing 67% of all the activity present in the Amazon of Ecuador. Other affected provinces are Napo, with 1,125 hectares; Morona Santiago, with 646; and Sucumbíos, with 610.

Deforestation caused by mining in the Ecuadorian Amazon is shown in red and yellow. Data: MapBiomas Amazonia, 2022. Map prepared by Ecociencia and MAAP.

Indigenous territories, representing 57% of Ecuador’s Amazon, are also being affected by mining; there this activity occupied 3,500 hectares in 2021. Six are the most affected indigenous territories, among them those of the Shuar indigenous people stand out.

These are some of the findings of the latest report by MAAP and the Ecociencia Foundation carried out with satellite images and data until 2021 from the Mapbiomas Amazonía satellite monitoring platform, managed by the organizations that make up the Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information (RAISG).

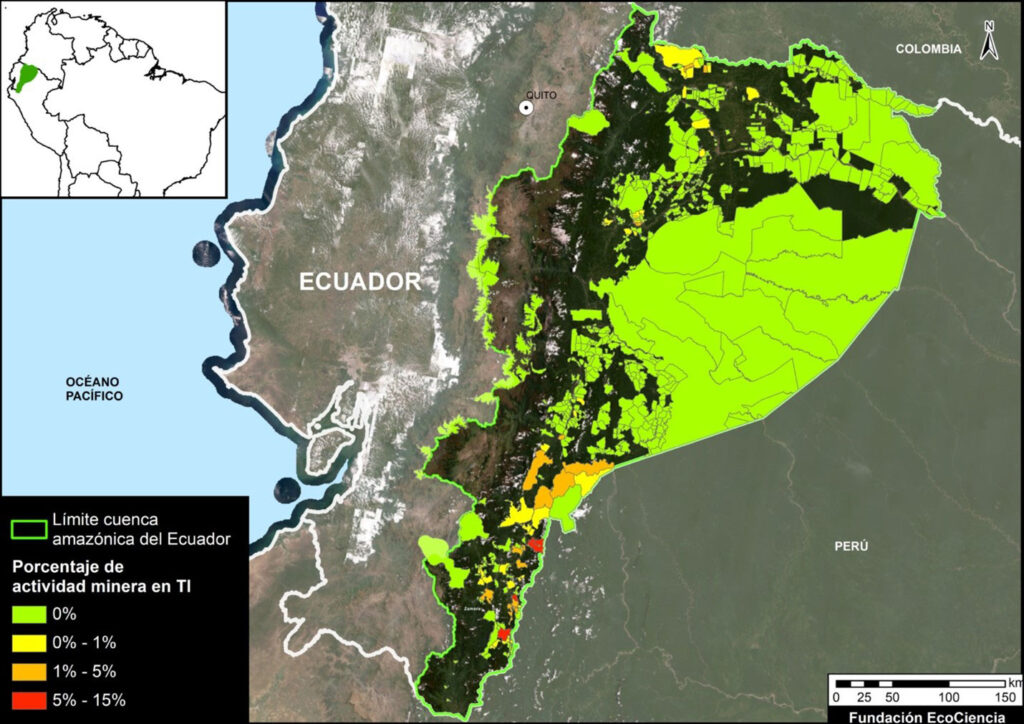

Presence of mining in Amazonian indigenous territories of Ecuador. Graphic: MapBiomas Amazonia 2022, Ecoscience and MAAP.

The organizations that led the study are the Andean Amazon Monitoring Project (MAAP) — a satellite monitoring program of deforestation and illegal mining led by the NGO Amazon Conservation — and the Ecociencia Foundation, focused on research and environmental protection in Ecuador.

Ecologist María Olga Borja, from Ecociencia, explains that this research, for the first time, allows us to have an understanding of the “dimension or magnitude of the mining problem in the Ecuadorian Amazon,” as well as understand the changes in this dynamic over time.

Photo: Punino community.

Mining that expands vertiginously

Mining expansion in the Ecuadorian Amazon has had consequences on the environment. The study points out that “mining is already an important direct cause of deforestation.” In the last year of measurement, 2021, the loss of forest cover increased by 46% compared to 2015, generating the loss of forest of 889 hectares, “a value not reached in any previous period,” the research states.

Jorge Villa, a specialist in geographic information systems and remote sensors at the Ecociencia Foundation, points out that mining has caused “deforestation, river pollution, and impacts on indigenous communities.”

The research highlights that Napo was the province with the greatest growth in terms of areas dedicated to mining. If in 2015 it had 270 hectares dedicated to this activity, by 2021, 855 were added, bringing it to 1,125 hectares, which means that the territory occupied for this activity increased 316%.

Borja points out that authorities should pay attention to local pockets of legal and illegal mining such as Punino and Yutzupino, in Napo.

In the range of colors red, orange and yellow, the percentages of mining presence in the territories of the Ecuadorian Amazon are observed. Map: Ecoscience, Mapbiomes Amazonia 2022, MAAP.

In Sucumbíos, on the northern border with Colombia, mining increased 750% in the years studied and the total area has already reached 610 hectares, after having 71 in 2015. Researcher Borja points out that mining in Sucumbíos is very close to the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve, a protected and indigenous area in the country. Furthermore, in this province, the speed of mining expansion is higher than in any other area of the Ecuadorian Amazon.

“There are at least three foci where mining is growing in different ways. The largest mining area has been reached in Zamora Chinchipe. There are the largest open pit mines. Since 2015 there has been an uptick in mining never seen before and the Podocarpus National Park has been affected,” denounces Borja. In Zamora Chinchipe, mining went from covering 1,261 hectares in 2015 to 5,034 in 2021.

The researcher explains that in Zamora Chinchipe there is significant biodiversity, which includes areas such as rocky elevations known as tepuis and that, being isolated, have high degrees of endemism, but that “they are beginning to be invaded by mining.”

The research findings were obtained thanks to the analysis of satellite images and data from the Mapbiomas Amazonía satellite monitoring tool, launched in early 2023 by the RAISG, of which Ecociencia is a part.

Borja highlights the importance of using technological innovation in the study methodology. “We use satellite images together with cloud data processing methodologies, as well as advanced algorithms to transform this large trove of information. For the first time, thanks to these advances, we have been able to reconstruct how the territory has been transformed.”

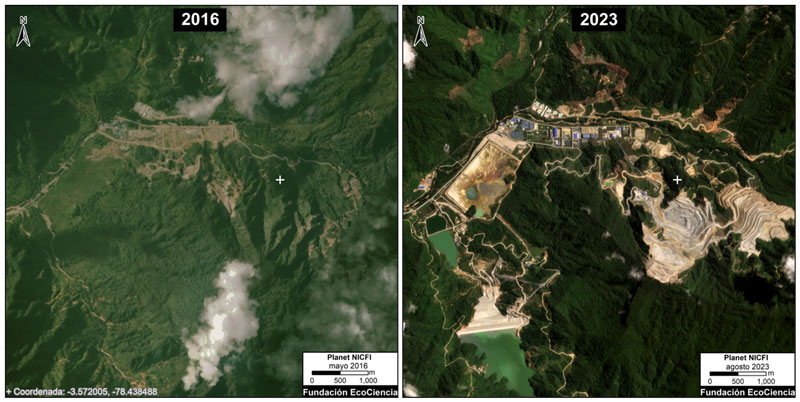

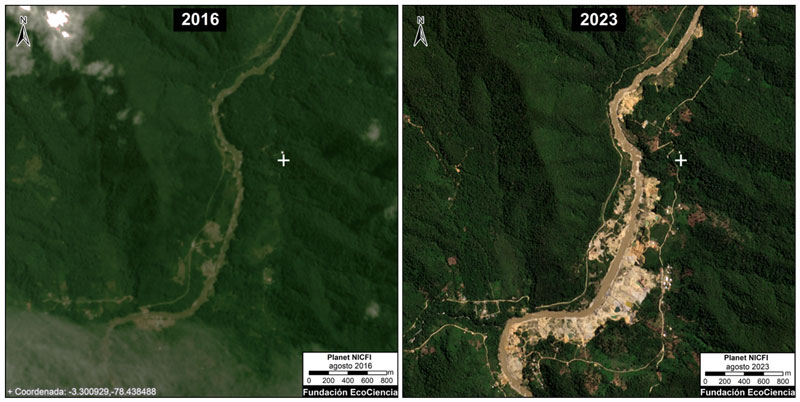

Mining progress in TI Tundayme and Development Project Area C between May 2016 (left panel) and August 2023 (right panel). Images from the Planet platform. Analysis carried out by EcoCiencia and MAAP.

Mining in indigenous territories

The report from environmental organizations also shows that the Amazonian indigenous territories of Ecuador are being affected by mining. At least 0.05% of its area is already occupied by activity.

Katy Machoa, former women’s leader of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), believes that in areas like Yutzupino, in Napo, mining is established because there are no job opportunities or access to education. “In that context, those who have the machinery enter and people allow it due to their lack of opportunities.”

Of the total mining surface in the Ecuadorian Amazon, at least 46.7%, that is, almost half, is located within indigenous communities.

In these territories, Borja points out, “mining is growing at an alarming rate:” if in 2015 there were 1,000 hectares with this activity, by 2021 the area was 3,500, which means an increase of 325%. This dynamic is very worrying, highlights the researcher since “indigenous territories are a bastion of defense of the natural resources of the Amazon and the culture of these peoples.”

Also, 61% of mining activity within indigenous areas is concentrated in six territories, all belonging to the Shuar people in the southeast of the Ecuadorian Amazon. In Tundayme and the “Development Project Area C” there is the largest mining presence, with 1,042 hectares, because the copper mining project called Cóndor Mirador, of the company Ecuacorriente SA, is located there.

The indigenous leader Machoa points out that the indigenous community has rejected the project in Tundayme because they believe that they have not been consulted or listened to. In the Ecuadorian Amazon, she says, there is a presence of Canadian and Chinese mining companies that have affected the communities and their nature.

Mining progress in the Churuwia community (TI Pueblo Shuar Arutam – PSHA) between August 2016 (left panel) and August 2023 (right panel). Images: Planet. Map: EcoCiencia and MAAP.

Researcher Villa points out that “in the territories of the Shuar peoples, the communities have said that for mining activity there has not been a process of prior, free, and informed consultation, so for these peoples, they are illegal, despite the fact that there are concessions of the state.”

The third indigenous territory with the largest mining presence is the Suar Kenkium Reserve, with 432 hectares “operated by the Kenkiu community company, Exploken Minera SA, it is the first gold extractive industry that belongs to Shuar groups.”

Then there is the Shaime Shuar community, where mining occupies 380 hectares on the edge of the Cuenca Alta del Nangaritza River Protective Forest.

According to the investigation, mining has also increased in the Wampiashu or Mariposa, Arutam-PSHA, Pacchus, Churuwia-PSHA, and Callamasa territories.

The study highlights that the next topic to investigate will be to determine “to what extent mining incursions into indigenous territories are legal or illegal.” Borja explains that they will seek to resolve this question in future studies: “At the moment we do not have sufficient data and tools to be able to discriminate when it is legal or illegal mining. “We’re going to work on it.”

The researcher points out that some mining concessions, although they have some permits, do not always have all the environmental licenses to carry out their exploitation. “In a concession area, there can also be illegal mining (if they do not comply with the law).”

Machoa says that regardless of whether it is legal or illegal mining, the most important thing is that the activities consult indigenous peoples and that they are not large scale to avoid damaging the environment.

* Main image: Illegal mining in the Bermejo River, Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve, Ecuador. Photo: Private archive.

This report was originally published in Mongabay Latam. It has been copyedited for clarity.

0 Comments