A sprawling society with pyramids, moats, and “forest islands” thrived from 500 to 1400 A.D. in the Bolivian Amazon.

The ruins of a vast ancient civilization that has remained hidden under the densely forested landscape of the Bolivian Amazon for centuries has now been mapped out in unprecedented detail, reports a new study.

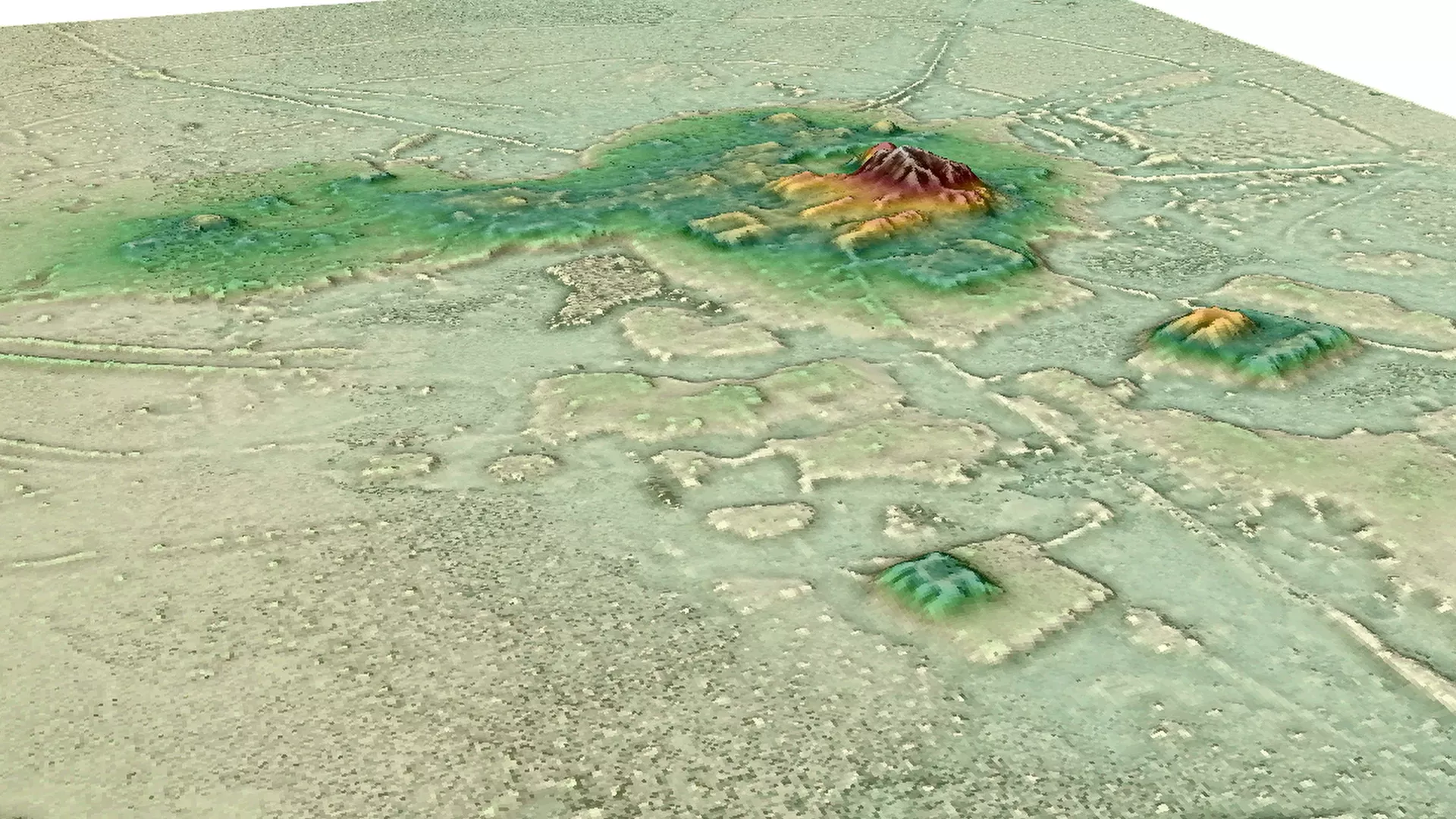

Millions of lasers shot from a helicopter have revealed evidence of unknown settlements built by a “lost” pre-Hispanic civilization, resolving a long-standing scientific debate about whether the region could sustain a large population.

The immense settlements stretch across some 80 square miles of the Llanos de Mojos region of Bolivia and include pyramids, causeways, canals, ramparts, elevated “forest islands,” and buildings arranged in ways that hint at cosmological worldview. The structures were built by the mysterious Casarabe culture, an Indigenous population that flourished from 500 to 1400 A.D. and came to inhabit some 1,700 square miles of the Amazon rainforest. The find is “mind blowing,” according to the leader of the research team.

While field expeditions and Indigenous knowledge have previously shed light on this region’s lost settlements, a remote-sensing technique called Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) has now exposed the enormous extent and tantalizing complexity of this civilization.

Scientists led by Heiko Prümers, an archaeologist at German Archaeological Institute in Berlin, used LIDAR to probe the remains of two large settlements called Cotoca and Landívar, along with 24 smaller sites, including 15 that were previously unknown to modern researchers. The results “indicate that the Casarabe-culture settlement pattern represents a type of tropical low-density urbanism that has not previously been described in Amazonia” and that “put to rest arguments that western Amazonia was sparsely populated in pre-Hispanic times,” according to a study published last week in Nature.

“The architectural layout of large settlement sites of the Casarabe culture indicates that the inhabitants of this region created a new social and public landscape through monumentality,” Prümers and his colleagues said in the study. “We propose that the Casarabe-culture settlement system is a singular form of tropical agrarian low-density urbanism—to our knowledge, the first known case for the entire tropical lowlands of South America.”

Old ideas give way to science

LIDAR scanners work by shooting thousands of infrared laser pulses every second at ground targets from aerial vehicles and recording the time it takes for the signal to bounce back. In this way, the method can generate minute details about topography that are beyond the range of other instruments. LIDAR is a particularly popular tool for archaeologists working at sites that are blanketed in dense vegetation, because they can expose details about past settlements that are difficult to spot or even access on the ground.

The Llanos de Mojos region is a lowland tropical savanna in the southwest of the Amazon basin. It has distinct wet and dry seasons each year — the driest months have no rain, but during the rainy season between November and April much of the area is flooded for months at a time.

While some of the buried structures at Llanos de Mojos were known, the new LIDAR data revealed a sprawling network of settlements linked by raised causeways that extend for miles across the verdant terrain and in which water was managed by a huge system of canals and reservoirs.

Spanish missionaries in the 16th century found only isolated communities living there, and scientists had supposed that the area’s pre-Hispanic population was the same. Earthworks were found in the 1960s, but many scientists disputed whether they were ruins or natural features.

“In one hour of walking, you can get to another settlement,” said Prümers. “That’s a sign that this region was very densely populated in pre-Hispanic times.” Prümers and his colleagues have studied the Casarabe ruins in the region, now part of Bolivia, for more than 20 years.

The two large settlements, Cotoca and Landívar, were protected by concentric defensive structures that include moats and ramparts. Numerous signs of civic and ceremonial life are embedded in more densely populated areas, such as 70-foot-tall conical pyramids and earthen buildings that curiously take the shape of the letter U.

“The scale and elaboration of civic-ceremonial architecture are key aspects of the large settlement sites,” Prümers and his colleagues said in the paper. “The orientation of the buildings that constitute the civic-ceremonial centers of the two large settlement sites is very uniform towards the north-northwest. This probably reflects a cosmological world view, which is also present in the orientation of extended burials of the Casarabe culture.”

While most of these monuments appear in more densely populated ruins, the scanned region may also have contained countless small hamlets that are too subtle to be detected by LIDAR, the team noted. Taken together, the new findings offer a captivating look at a society that thrived in this forested region for centuries, building massive agricultural and aquacultural infrastructure that sustained a rich social and ritual life.

“The scale, monumentality, labor involved in the construction of the civic-ceremonial architecture and water-management infrastructure, and the spatial extent of settlement dispersal compare favorably to Andean cultures and are of a scale far beyond the sophisticated, interconnected settlements of southern Amazonia, which lack monumental civic-ceremonial architecture,” the researchers said in the study.

“As such, the data contribute to the discussion of the global wealth of early urban diversity and will help to redefine the categories used for past and present Amazonian societies.”

0 Comments