by Antonio José Paz Cardona on February 23, 2024

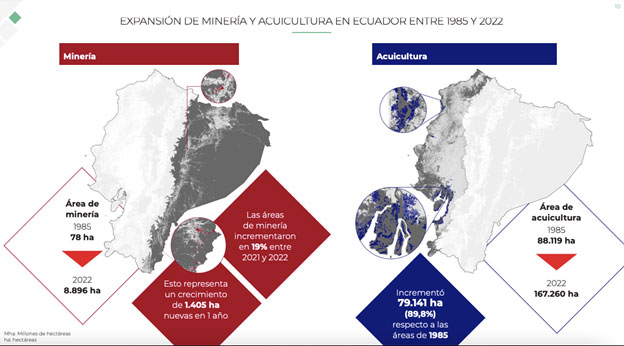

- In the Ecuadorian Amazon, the accelerated growth of mining is worrying. In 2022 the activity reached 8,896 hectares. Between 2021 and 2022 alone, 1,405 new hectares were detected, equivalent to almost 2,000 professional soccer fields.

- The advance of activities such as forestry in the mountains and aquaculture on the coast have expanded between 1985 and 2022. At this time the country has more hectares with aquaculture than with mangrove ecosystems.

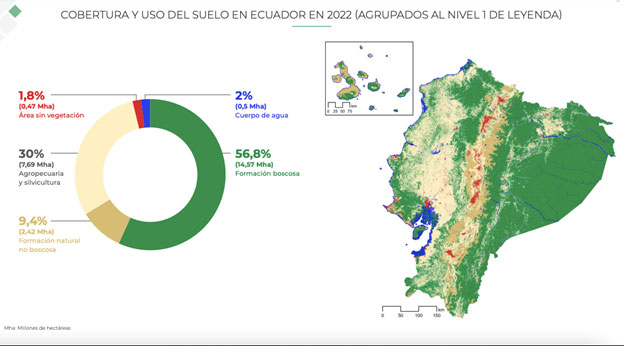

In 38 years (1985 – 2022) Ecuador lost 1,160,000 hectares of natural cover such as forests, mangroves, grasslands, rocky outcrops, among others. These are some of the findings detected thanks to MapBiomas Ecuador, the first platform that collects almost forty years of data on land cover and use in the country.

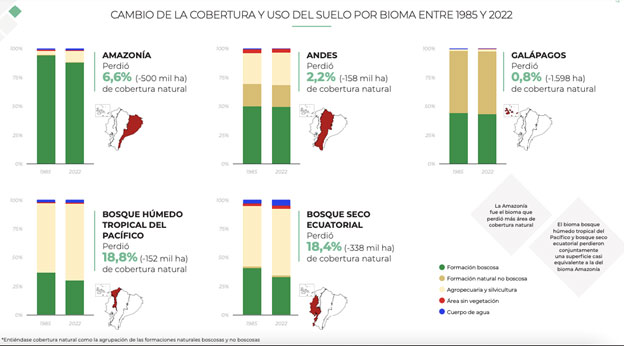

“In the analysis, the country was divided into five biomes: Amazon, Andes, Galapagos, Equatorial Tropical Dry Forest and Pacific Humid Forest. Almost half of the forest loss in these 38 years occurred in the Amazon biome [500,000 hectares, representing 6.6% of the forests of the Ecuadorian Amazon]. It is where we have the most forests, but it is also where we are losing them the most,” says María Olga Borja, geographer and part of the MapBiomas team that worked on the data analysis.

Credit: MapBiomas Ecuador.

Agriculture and mining in the Amazon

One of the data that draws most attention in the MapBiomas Ecuador analysis is that 1,080,000 hectares of forest formations were lost between 1985 and 2022, but the areas of agricultural and forestry use—cultivation and maintenance of forests, mainly for commercial—grew in almost the same proportion (1,070,000 hectares), which represents an expansion of 16% for these activities in 38 years.

Anthropic land uses increased by 486,000 hectares (154%) in the Ecuadorian Amazon during that period. “The Amazon is the new agricultural frontier […] For a long time this area was seen as non-productive, but because other soils – such as those of the Ecuadorian tropical dry forest – have already been occupied, now efforts are being made to encourage production in The Amazon”.

The specialist highlights that the region where the country’s largest forestry heritage is located is also the place where “what we are seeing are greater losses and greater agricultural expansions.”

Wagner Holguín, coordinator of Mapbiomas Ecuador and member of the EcoCiencia Foundation, finds the increase in mining in the Amazon worrying. “There has been exponential growth. In the last five years we are talking about growth that is even above 300%,” he assures.

Illegal mining in the Bermejo River, Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve, Ecuador. Photo: Private archive.

MapBiomas figures indicate that in 1985, 75 hectares with mining activity were detected, while in 2022 the number was already 8,896 hectares, equivalent to more than four times the city of Latacunga, located in the central area of the country.

The greatest expansion of mining activity has occurred in recent years; between 2021 and 2022 alone, 1,405 new hectares of mining were identified.

María Olga Borja mentions that, currently, illegal mining in the Ecuadorian Amazon is no longer artisanal but mechanized, which leads one to think that there is a very large investment behind this activity. “This mining is promoting the transformation of very extensive areas, not only on the edges of rivers, which are super valuable and ecologically unique ecosystems, but it is causing deforestation. “This growth in areas affected by mining has intensified in recent years.”

Borja explains that, based on the data, they identified a first peak in forest loss due to mining around 2016, and that it was related to the opening of Ecuador to large-scale mining. What is currently being observed, he clarifies, is a consequence of “illegal and totally mechanized mining.”

Credit: MapBiomas Ecuador.

A source from the area, who prefers anonymity due to security problems, assures that the mining expansion is related to a lack of investment in the Amazon region, absence of work options for people and a post-pandemic economic crisis still in force, “ “which has become a breeding ground for what is happening now in Ecuador, with a strong entry of cartels that are financing illegal activities, including illicit mining in the Amazon, to launder money.”

An analysis of forestry and aquaculture

MapBiomas analysis shows that the Equatorial Tropical Dry Forest and the Pacific Humid Forest also had significant losses. The first saw 338,000 hectares of natural cover disappear (18.4%) and the second 152,000 hectares (18.8%).

The figures are alarming because these biomes concentrate a large part of the Ecuadorian population, for many decades they have been transformed at great speed, but the little that remains continues to be lost. “If we add the figures from both biomes, the number is almost comparable to what was lost in the Amazon,” says Borja.

“At this moment the loss of a dry forest or a humid forest in the Pacific represents much more in terms of loss of biodiversity, without this meaning that what is happening in the Amazon is not worrying,” says Borja.

The greatest pressure on the five biomes is agricultural, and although there is a varied range of crops, significant areas of corn have been detected in the dry forest and oil palm in the humid Pacific forest.

There are about 20,000 hectares planted with oil palm in the Shushufindi canton, according to figures from the Sucumbíos Prefecture. Almost 15,000 belong to Palmeras del Ecuador. The city’s economy depends, to a large extent, on this activity. Photo: Alexis Serrano Carmona.

In the Andes, MapBiomas Ecuador found a significant increase in forestry – cultivation and maintenance of forests, mainly for commercial use –, an activity that grew by 77% in the last 38 years, going from 43,060 hectares in 1985 to 76,282 by 2022.

“It is important to identify these areas because it is very different to talk about forestry trees than to talk about a natural forest. Forestry is normally related to introduced species that are not naturally native to the environment in which they are found. For example, here there is a lot of pine and eucalyptus,” says Wagner Holguín.

Borja adds that it is worrying that forestry, generally represented by commercial monocultures, is advancing rapidly on paramo areas that are naturally non-forest areas, that is, they do not have forests. For the specialist, this is serious because the moors are very restricted ecosystems that are being heavily attacked by burning and fires.

The MapBiomas Ecuador analysis also identified a worrying increase in aquaculture—cultivation, breeding, and harvesting of fish, shellfish, algae, and other organisms in all types of aquatic environments—on the coast, where mangroves have been one of the biggest sufferers.

Credit: MapBiomas Ecuador.

Mangroves occupied 157,000 hectares in 2022, however, between 1985 and 2022 this ecosystem had a loss of 16.4%. For its part, aquaculture doubled its extension, going from 88,000 hectares in 1985 to 167,000 in 2022. One of the most alarming data from the analysis is that there is currently more aquaculture than mangroves in Ecuador.

For Holguín, the growth of aquaculture responds to a reality of the country: shrimp is one of the main export products.

Holguín says that it is important to address issues such as the treatment of water in shrimp ponds, since in the production process fresh sea water enters the pools, various products are added there for the growth of the shrimp and these waters return. to go out to sea. In addition, it is necessary to analyze how much pressure this aquaculture is having on the mangroves, ecosystems that, due to their flood ability, become ideal places for the establishment of this activity. “In general terms we are not against any activity, as long as it is carried out in a sustainable way and does not threaten natural aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems,” he comments.

MapBiomas specialists assure that the objective of the platform is to provide figures and provide a broad overview of what is happening with land uses in Ecuador. That these inputs can be used by people, organizations and the government to carry out an in-depth analysis that allows them to make correct decisions in the management of the environment and the productive activities of the country.

*Main image: Oil palm in Ecuador in 2019. Satellite image of African palm plantations to analyze changes in vegetation cover in San Lorenzo. Photo: Rodrigo Sierra.

This report was originally published in Mongabay Latam.

Palm Oil is the most unhealthy oil for human consumption and should be banned!