Nearly 240,000 hectares were deforested in Ecuador during those years, according to a MapBiomas report.

- During this period, the rate of loss of natural cover increased in the country, which is causing concern among experts.

- Mining, livestock farming, selective logging, road construction, and monocultures promote deforestation in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

- Deforestation is putting increasing pressure on protected areas and indigenous territories, which have been barriers against this threat.

Between 2020 and 2024, Ecuador lost 239,849 hectares of forest, according to data analyzed by the EcoCiencia Foundation team for MapBiomas Ecuador. This is equivalent to deforesting an area similar in size to Luxembourg. The loss is directly correlated with the growth of agriculture and pastureland, which increased by 311,582 hectares during the same period.

The situation is considered “quite worrying” by Pablo Cuenca, director of the Global Change Laboratory and co-director of the Tropical Ecosystems and Global Change research group at the Ikiam Regional Amazonian University. He explains that after having a gross deforestation rate of 0.93% between 1990 and 2000, the figure had dropped to 0.75% between 2018 and 2020.

However, this trend has now reversed, with the deforestation rate at 0.78%. This equates to the disappearance of 95,000 hectares of natural cover each year, an area roughly 280 times the size of New York’s Central Park.

Oil palm plantations in the Chocó region, an area of significant biodiversity. Photo: courtesy of Gustavo Redín

Wagner Holguín, coordinator of MapBiomas Ecuador, explains that agricultural expansion remains the main driver of land-use change in the country. Productive activities are also covering natural areas devoid of vegetation, the expert points out.

Morona Santiago, in the southern Ecuadorian Amazon, was the most affected province, with 69,187 hectares deforested. It was followed by Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas, on the northern coast, with 45,035 hectares; and Zamora Chinchipe, the southernmost Amazonian province, with 40,679 hectares. Manabí, Bolívar, Cotopaxi, and Loja each registered more than 24,000 hectares deforested. At the same time, these provinces also saw the largest increases in agricultural land.

MapBiomas’ latest report is based on its third data collection, which this time included information on the expansion of forestry and banana cultivation. According to the Ecociencia technician, this data aims to provide exporters and the country with the information needed to address the European Union’s (EU) zero-deforestation regulation, which requires that products exported to the EU must not have been produced on land deforested after December 31, 2020.

A banana plantation in the province of Los Ríos, the largest producer of this fruit in Ecuador. Photo: courtesy of the Los Ríos Prefecture

Between 2020 and 2024, forestry was responsible for the deforestation of 5,582 hectares. Meanwhile, between 1985 and 2024, banana cultivation experienced a 182% increase, growing from 60,045 hectares to 169,438 hectares. The coastal provinces of Los Ríos, Guayas, and El Oro account for 94% of the cultivation. Holguín highlighted the expansion of this fruit in Santa Elena, beginning in 2010. This was surprising, he explained, because the province has a dry ecosystem with few water sources.

The factors of deforestation

Cuenca explains that agriculture is driving land-use change through crops such as oil palm, bananas, pitahaya, and cacao. Following the collapse of cacao production in Africa, there was a boom in the Amazon, in response to high prices for this commodity, the academic notes.

Balsa wood, used as a raw material for wind turbine blades, also experienced a boom, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic. This resulted in the logging of this species, as well as the deforestation of Amazonian forests to cultivate it.

Along the road to Loreto, community members turned to cultivating balsa, a fast-growing species. Photo: Courtesy

For Cuenca, other factors contributing to deforestation were the construction of roads through the Amazon rainforest, both by local governments and illegal actors, and the expansion of illegal gold mining.

In Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas, deforestation is driven by multiple factors, according to Marisol Angulo, an environmental educator at the San Jorge Agroecological Farm. In 2024, the National Assembly declared the province the meat capital of Ecuador, due to its large production of beef, pork, and chicken. For Angulo, this declaration promotes the replacement of forests with pastureland for livestock farming.

The environmental educator and nursery owner also notes that monocultures impact natural vegetation cover. Currently, she says, large expanses of pineapple and cacao plantations are visible. In fact, the province is one of the main producers of pineapple for export, contributing to Ecuador’s position among the South American countries with the largest share of this market.

Protected areas and indigenous territories remain barriers against deforestation, according to Holguín. However, the threat is getting closer and, in some cases, is already within protected areas, such as the Yacuambi Protected Area and the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve, spaces where mining is prohibited, but where it is suspected that illegal actors have caused deforestation to extract alluvial gold.

Pig farms in Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas, one of the provinces with the largest pig population in the country. Photo: Xavier León

Cuenca points out that buffer zones are no longer fulfilling their role. In a study he participated in, it was found that up to 25.5% of the accumulated deforestation between 1990 and 2018 occurred in these buffer zones. Therefore, Cuenca believes it is essential that conservation policies create mechanisms to protect buffer zones.

Mining threatens the Amazon

Morona Santiago and Zamora Chinchipe, two of the provinces with the greatest loss of forest cover, are located in the Ecuadorian Amazon. While the main driver of deforestation is agricultural activity, mining is also a cause for concern, as it not only leads to forest loss but also causes serious environmental and health impacts due to the use of chemicals such as mercury.

According to MapBiomas Collection 3, in 2024, 71% of mining—both legal and illegal—was located in the Amazon, covering approximately 11,000 hectares. Zamora Chinchipe had the largest area affected by mining, with 6,802 hectares. It was followed by Napo, with nearly 2,000 hectares, and Morona Santiago, with around 1,800 hectares.

Illegal mining in Zamora Chinchipe has caused deforestation along riverbanks, flooding, and the release of toxic substances such as mercury and cyanide, which affect water quality. Photo: Courtesy of José Dimitrakis / Vistazo Magazine

A geospatial analysis led by the Geoinformation and Remote Sensing Laboratory of the Higher Polytechnic School of the Coast (ESPOL) found that between 2018 and 2023, legal and illegal mining in Zamora Chinchipe was concentrated in the waterways of the Zamora and Nangaritza rivers. It also found that the most affected conservation units were Podocarpus National Park and El Cóndor Biosphere Reserve. Furthermore, it identified both concessionary and illegal mining taking place on titled Indigenous territories.

Illegal mining activities have also increased around the Alto Nangaritza Protected Forest and within the Podocarpus National Park, according to Jorge Villa, a Geographic Information Systems specialist at the Ecociencia Foundation.

Meanwhile, in Morona Santiago, illegal mining has been growing, mainly in the south of the province, with “considerable force,” according to Villa.

Livestock farming, logging and monocultures

Fernando Espíndola, a geographer residing in Morona Santiago, explains that the increase in human settlements, the construction of roads, the advance of the livestock frontier and logging are the main culprits behind the loss of natural cover in the province.

A drone shot shows the road crossing through flood-prone areas. Photo courtesy of Achuar community monitors

There, deforestation has been concentrated in the Taisha canton, where land use dynamics began to change about 50 years ago when settlers arrived to establish cattle ranches, transforming the forest into pastureland, according to Espíndola. In recent years, the geographer asserts, Indigenous people from the Shuar and Achuar territories have been leasing pastureland to the settlers who continue to arrive.

In 2016, a road was finally built to connect the canton to the main Amazonian cities. This road, although rudimentary, facilitated the logging of valuable hardwoods.

The problem worsened when, between 2022 and 2025, local governments opened 62 kilometers of roads in Achuar territory without environmental permits or technical studies. More illegal loggers arrived, sparking deadly disputes between the Indigenous residents who want to conserve the territory and those who argue that selling timber is the only way to generate income for the inhabitants of one of the poorest areas in the country, with the fewest basic services.

“The demand for timber in Taisha is extremely high among timber traders,” Espíndola asserts. “The communities need money for transportation, for schools, for trips to Macas [the provincial capital],” he adds. However, since these are villages that have lived off their environment for centuries, being exposed to commercial dynamics now has been difficult, so selling timber is the easiest option, according to the geographer.

Palora is considered the tea and pitahaya capital. Photo: courtesy MAAP

On the other hand, in the northern part of the province, in the Palora canton, pitahaya cultivation caused the deforestation of 248 hectares of rainforest between 2019 and 2023, according to data from report 194 of the Mapping of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP), by Amazon Conservation. The increase in the fruit’s price led to the cultivated area growing from less than five hectares in 2000 to more than 3,000 hectares in 2023, Mongabay Latam reported. “It is expected to grow to 4,000 hectares by 2026,” Espíndola notes.

Policies and socioeconomic challenges

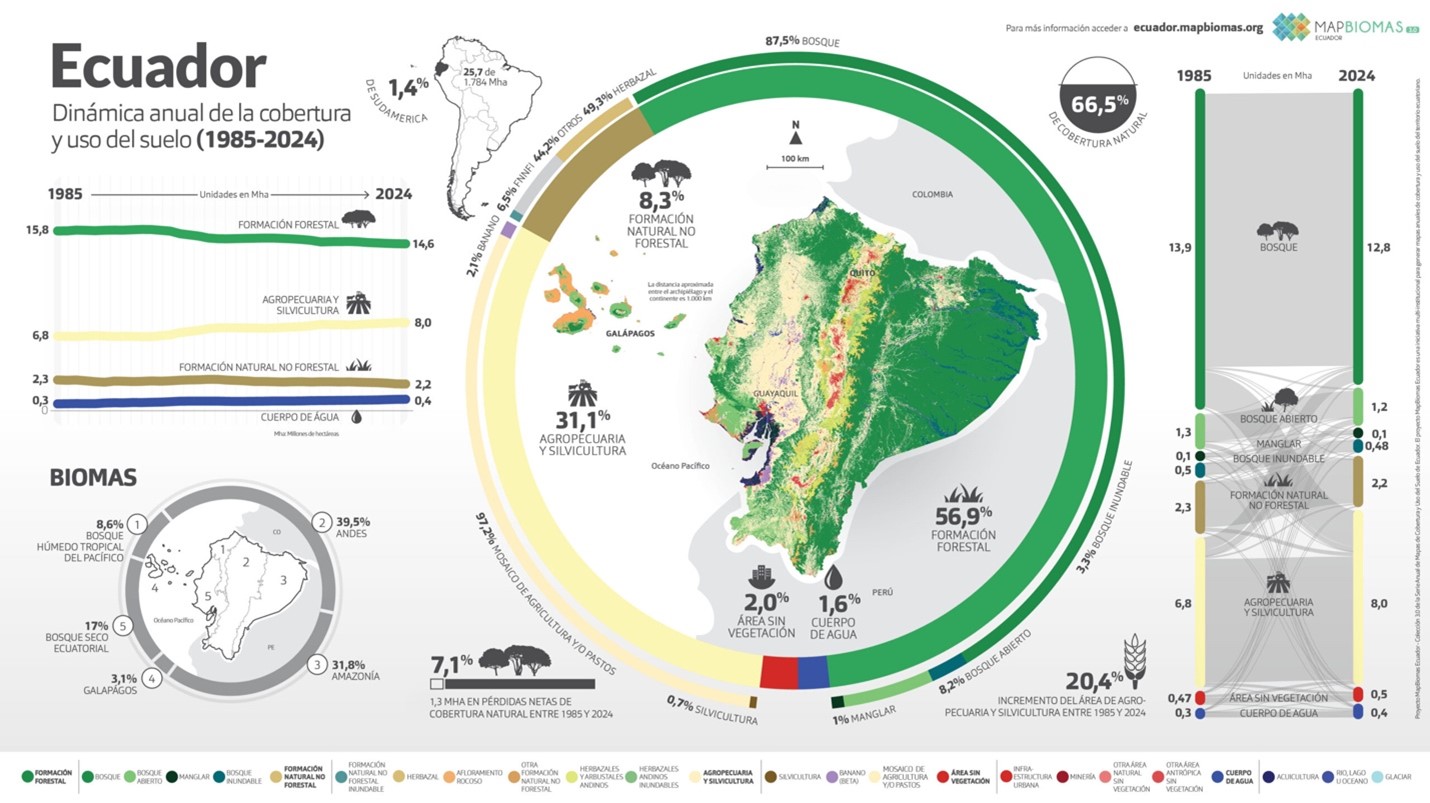

Key data from Collection 3 of MapBiomas Ecuador. Image courtesy of MapBiomas

Between 1985 and 2024, natural land cover decreased by 1.31 million hectares, while human-modified land cover increased by 1.4 million hectares, according to the MapBiomas Collection 3 report. Specifically, Ecuador lost 1.21 million hectares of forest and gained 1.19 million hectares of agricultural land.

“The figure demonstrates both the pressure on ecosystems and the need for comprehensive policies that harmonize production and conservation,” says Cristina Aguilera, an analyst at MapBiomas Ecuador.

Angulo agrees and points out shortcomings in the environmental management of Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas. “There used to be a provincial environmental committee, where ordinances were created to minimize the advance of forest destruction, but now they don’t give it any importance,” she asserts. The environmental educator and nursery owner believes that the creation of strong environmental laws is necessary.

Intervention by the provincial government of Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas on a road used daily to transport timber, livestock, and other products: Photo: courtesy of the Provincial Government

Espíndola, on the other hand, believes that environmental awareness is lacking in Morona Santiago, one of the country’s largest and greenest provinces, where resources seem to be endless. He also criticizes the management of provincial and cantonal governments, which prioritize road construction without oversight when there are urgent needs in health and education.

Both experts remain hopeful that changes will be made to protect the environment and natural resources. Angulo is part of the San Jorge Agroecological Farm, which was declared a Conservation and Sustainable Use Area in 2025 and from where conservation is promoted.

Meanwhile, Espíndola highlights initiatives such as that of the Chankuap Foundation, which provides technical assistance to Shuar, Achuar and mestizo producers in the development of products that do not generate impacts on the forests.

Main image: Deforestation for oil palm plantations in the Amazon rainforest, in the province of Orellana, Ecuador. Photo: Rhett A. Butler

0 Comments