Inside one of southern Ecuador’s busiest referral centers, doctors and nurses say emergency care is collapsing under supply failures.

A protest born inside the emergency room

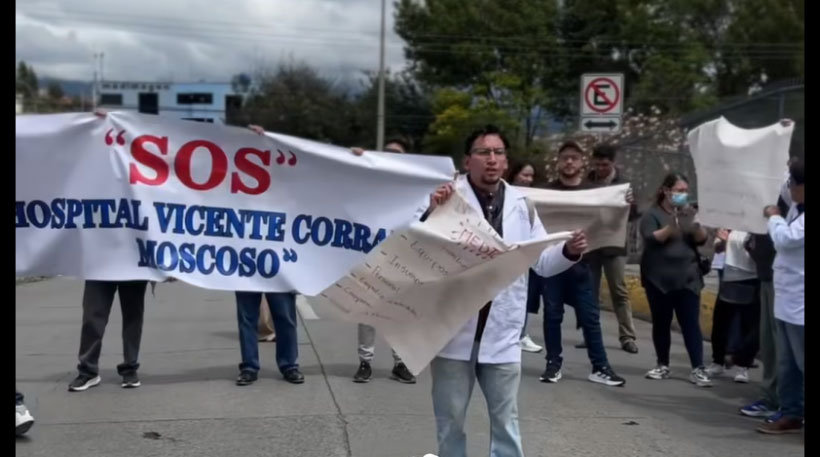

White coats and surgical aprons replaced the usual bustle of stretchers outside Vicente Corral Moscoso Hospital on January 9th, as doctors, nurses and technicians walked out to make visible what they say has been hidden for months inside Cuenca’s largest public medical center. Their message was blunt: the hospital is running out of the medicines and supplies that keep people alive.

Healthcare workers said the demonstration was not about salaries or working conditions, but about the patients arriving every day from across Azuay and neighboring provinces who are being told they must buy their own gloves, sutures and even lifesaving drugs. Vicente Corral is the main referral hospital for Loja, El Oro and Morona Santiago, meaning its shortages ripple far beyond Cuenca itself.

Placards demanding real solutions — not temporary fixes — reflected growing anger among staff who say government announcements about deliveries do not match the reality on the wards.

“We can’t do anything for them”

In the emergency department, the consequences of those shortages are immediate. Alberto Martínez, an emergency physician at the hospital, described a unit stripped of the basic tools needed to respond to heart attacks, strokes and seizures.

During a shift on January 8th, Martínez said nearly 200 medications were already unavailable and another 300 were close to running out. That means doctors are forced to improvise, delay treatment, or send families racing to private pharmacies to find what the hospital should already have.

“If someone comes in with a heart attack, we can’t do anything. If it’s a stroke, we can’t do anything. If we need to sedate someone or stop a seizure, we can’t do that either,” Martínez said, explaining that this situation is no longer occasional but routine inside the emergency room.

Those words, repeated by colleagues across different departments, formed the emotional core of the protest: trained professionals watching preventable suffering unfold while they stand powerless.

A system still in crisis after the emergency ended

The protest also reopened a debate about how Ecuador’s health emergency was handled. The Ministry of Health declared a national emergency in September due to widespread shortages of medicines and medical supplies. That emergency was lifted on November 28, 2025, even though many of the procurement processes launched during that period failed to deliver what hospitals actually needed.

Staff at Vicente Corral say the decision to close the emergency left them exposed just as supply chains were breaking down. What was presented as a temporary crisis has instead hardened into a daily operational failure.

By early January, complaints from patients waiting in long lines or being sent out to buy their own medications had merged with the frustration of hospital workers who say they are being asked to perform modern medicine with empty cabinets.

Patients forced to pay to be treated

In the surgical wards, the shortages look different but are just as damaging. Nurse Carlos Gómez said families are now routinely told to purchase everything from disposable gloves to sutures before procedures can move forward.

“We’ve reached a breaking point,” Gómez said, explaining that from a practical standpoint the hospital simply does not have the medicines or supplies required to function normally. What should be provided by the public system is instead being paid for out-of-pocket by people who often arrive already struggling financially.

For patients referred from rural areas or smaller provincial hospitals, that burden can be crushing, delaying surgeries and exposing them to additional risks.

Government figures versus hospital reality

The Ministry of Health has insisted that supplies are being delivered. In a statement released on January 8th, the ministry reported that 236,446 units of essential and vital medicines had been distributed to stock hospital pharmacies.

According to the ministry, the shipments included drugs such as lidocaine, cephalexin, clindamycin, diclofenac, levetiracetam, rivaroxaban, atorvastatin, metronidazole and quetiapine — a list that on paper covers everything from anesthesia and antibiotics to seizure control and psychiatric treatment.

But hospital staff say those figures do not reflect what is actually on their shelves. Martínez directly rejected claims that essential medicines and supplies have arrived in sufficient quantities, saying doctors and nurses continue to experience shortages every day.

The disconnect between official statements and clinical reality is what finally pushed many to protest, fearing that without public pressure the situation would continue to deteriorate behind hospital walls.

A regional lifeline under strain

Vicente Corral Moscoso is not just another hospital; it is the backbone of public healthcare for southern Ecuador. When its emergency room stalls, patients from multiple provinces have nowhere else to go.

As ambulances continue to arrive, staff say the question is no longer whether the system is strained, but whether it is being allowed to fail quietly. For doctors and nurses who took to the streets this week, the goal was simple: to make sure the collapse is seen — and felt — before more lives are lost inside a hospital that was built to save them.

0 Comments